This pandemic offers a moment to reflect on the sprawling economic connections that link us, and even to critique them and the resultant human effects on the globe, in terms of climate, environment, and even public health. That these discussions are not happening in Japan may reflect the impression here that things are completely under control in terms of domestic COVID-19 infection.

At least according to the numbers, Japan does seem to have successfully limited the spread of the disease. Japan’s numbers of COVID-19 infection are incredibly low. As of 10pm March 23rd, there were 1107 officially recognized cases, and only 42 deaths.

The three pillars of Japan’s official containment strategy have been:

- Early discovery of infection clusters.

- Concentrate medical care on those with serious symptoms

- Change citizens’ behavior [1]

Regarding the first, early discovery of infection clusters, anyone who has followed the main Japanese news channels—the public broadcaster NHK, the Asahi Shimbun, the Yomiuri Shimbun— would see only a very small number of infections per population, all organized around identified clusters or made up of people recently returned from abroad.

There is evidence that these numbers are skewed, however, since obtaining a test is limited to:

- Those with prolonged contact with already identified cases of COVID-19 and who have a fever of 37.5 degrees Celsius or respiratory symptoms.

- Those recently returned from a COVID-19 “hotspot” and who have a fever of 37.5 degrees Celsius or respiratory symptoms.

The limited testing policy has been criticized, particularly in light of WHO’s directive to “test, test, test.” Kurokawa Kiyoshi, the chair of the Fukushima Nuclear Accident Independent Investigation Commission, has gone on the record that he fears that the Japanese government is actually paralyzed in the face of this new, unprecedented crisis.[2]

According to the Health Ministry, however, the justification for limited testing has been to bolster the second part of the strategy: to direct all medical resources to the most severe cases. Japan argues that if they tested everyone who wanted a test, hospitals would be overwhelmed, as was the case in Italy.

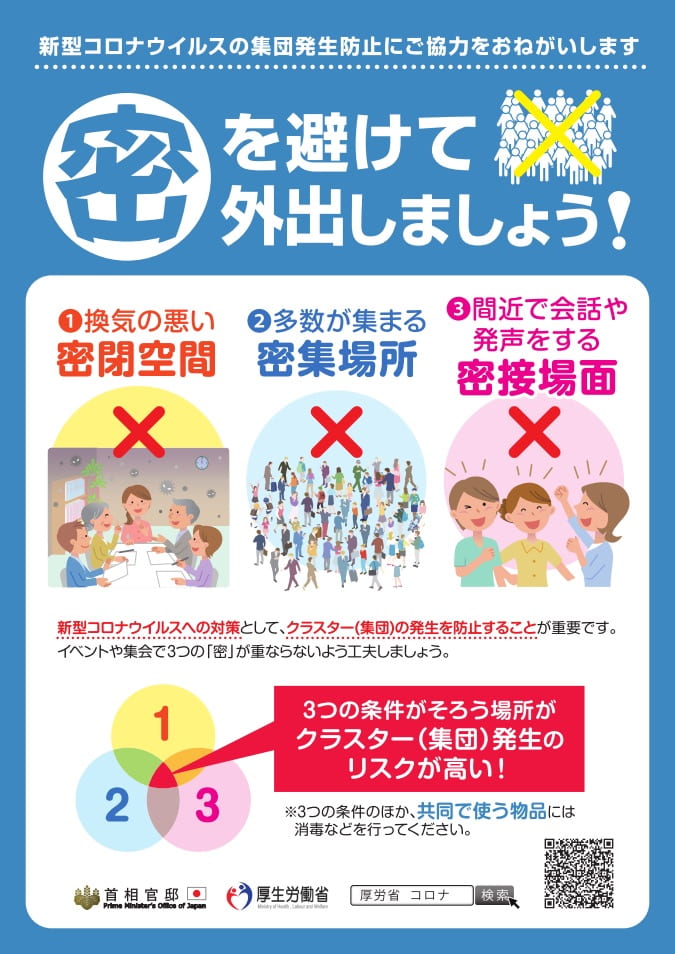

Finally, regarding “changing citizens’ behavior,” a frequently invoked phrase is “self-restraint” (jishuku). The government has distributed signs about effective hand washing and cough etiquette, and is also advising that people avoid the “three densities (mitsu)”:

- Closed spaces with bad ventilation

- Dense gathering places with many people

- Close talking

These directives are based on what epidemiologists have found in Japan regarding transmission: the clusters that they have currently identified—and keep in mind that with limited testing it is hard to know that this is the actual limit to the community spread—occurred within crowded, poorly ventilated spaces: a trade show in Hokkaido, a gym in Nagoya.

While other major cities in the global north are issuing directives that forbid their citizens from going outside for anything other than essential activities, the Japanese government is proposing “let’s go outside!” as an alternative to gathering in closed spaces. If the clusters of COVID-19 infection in Japan are indeed contained, this may be fine. If not, epidemiological evidence from other places suggests that this may be foolhardy.

In any case, the view from Tokyo is this: while people have been discouraged from setting out the usual blue tarps and lingering under the cherry blossoms—now in splendid full bloom—there are still an enormous number of people gathering at blossom-viewing spots. Cafes are still open and friends still sit close and gossip. Stores have no more masks in stock, so fewer and fewer people wear masks in public. Thousands attended a K-1 fighting tournament, crowding an arena in Saitama on the same day that prefecture confirmed a new infection in man in his 60s with no history of travel to known hotspots, nor recorded contact with existing cases. Tens of thousands queued up to see the Olympics flame—perhaps to, as directed by the Tokyo Games’ slogan, become “United By Emotion.” What that emotion uniting Japan to the world is, we still just can’t say.

– 24 March 2020

Chelsea Szendi Schieder is a historian of contemporary Japan and an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Economics at Aoyama Gakuin University in Tokyo, Japan. Her book, Co-Ed Revolution: The Female Student in the Japanese New Left, is forthcoming on Duke University Press.

[1] https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/special/coronavirus/view/

[2] https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/03/12/national/science-health/coronavirus-japan-paralyzed-fukushima/#.XnlIb9Mza1v

* * *

The Teach311 + COVID-19 Collective began in 2011 as a joint project of the Forum for the History of Science in Asia and the Society for the History of Technology Asia Network and is currently expanded in collaboration with the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science(Artifacts, Action, Knowledge) and Nanyang Technological University-Singapore.

![[Teach311 + COVID-19] Collective](https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/teach311/files/2020/04/Banner.jpg)